During 1779, armies under the command of American General George Washington and British General Sir William Clinton were locked in a strategic stalemate. Washington’s Continental forces were deployed around Middlebrook, in northern New Jersey, while Clinton’s forces defended New York. The entry of the French into the war as American allies had shifted the strategic initiative and caused the British government to order Clinton to dispatch significant forces to the West Indies and southern colonies. The reduction in his available forces hampered Clinton’s efforts to bring Washington to a decisive engagement. Hoping to lure Washington out of the protection of his strong defensive positions at Middlebrook, Clinton decided to launch an attack north from New York to threaten the important American supply routes that crossed the Hudson River at Kings Ferry. Clinton’s attack was also intended to establish a base of operations that would allow an attack on the American fortress at West Point. In late June 1779 Clinton moved men and material into position for his thrust up the Hudson while Washington cautiously responded by moving his army north to positions intended to respond to the British advance. Clinton struck on 3 July 1779, capturing the strategic Kings Ferry crossing of the Hudson River along with American forts at Stony Point and Verplank’s Point.

Rather than react as Clinton had hoped, Washington remained safely deployed in the Watchung Mountains. Hoping to entice Washington to leave his sanctuary, Clinton ordered Major General William Tryon to attack American supply stockpiles and privateer bases in Connecticut. Despite burning Fairfield and New Haven, capturing or destroying large quantities of supplies and ships, Tyron’s raid did nothing to entice Washington to respond.

Although he had established a strong position at Stony Point, Clinton still lacked the resources to strike further up the Hudson at West Point without exposing New York City to a sudden attack by the Americans. The delay in the anticipated return of 5,000 men from the West Indies and expected reinforcements from England continued to flummox Clinton and after the return of Tyron’s Connecticut raiding party Clinton returned to New York to consider his options.

Washington had not been inactive throughout the period of the British attacks. Whilst anxious about maintaining communications between the New England states and the Middle Colonies across Kings Ferry, and protecting West Point, Washington also recognized the importance of protecting his Continental Army. He clearly understood Clinton’s desire to engage the Americans at a disadvantage and was not deceived by Clinton’s attempts to goad him into a precipitous action. At the same time Washington understood that the loss of Kings Ferry would create long term logistical problems for his army and that the British capture of West Point would have catastrophic impacts on American morale.

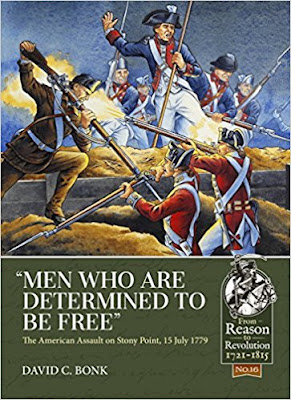

Soon after the British capture of Stony Point Washington began to develop an audacious plan to recapture the strongpoint and restore American fortunes. After organizing an elite force of light infantry, Washington assigned command to Brigadier General Anthony Wayne. Washington and Wayne spent several days observing the British position at Stony Point and collecting intelligence on British defenses. Washington proposed a night time assault and worked with Wayne to finalize plans for the attack. At midnight on 15 July, 1779 Wayne led 1,300 picked men against the British defenders of Stony Point. The British force included the 380 men of the 17th Foot and elements of the Loyal American provincial regiment and 71st Highlanders as well as Royal Artillery with 15 cannon deployed to defend the hilltop position. Attacking in two columns with unloaded muskets, the Americans used their bayonets to overwhelm the British defenders. In little over one hour the American light infantry captured Stony Point. 63 British defenders were killed, 61 wounded and 543 captured. American losses were 13 dead and 63 wounded. Wayne, although slightly wounded early in the assault, demanded to be carried in to the British positions and early on the morning of 16 July 1779 prepared a brief report for Washington detailing the American success.

With news of the American victory Washington quickly rode to the fort to congratulate Wayne and his men. Recognizing that he had neither the troops nor the resources needed to defend Stony Point against an expected British counter attack Washington ordered all supplies and arms to be removed, prisoners marched into captivity and the fortifications destroyed. Although the British did successfully reoccupy Stony Point several days later, the Americans trumpeted their unexpected victory and a chagrined General Clinton concluded a further offensive up the Hudson River towards West Point would be pointless.

No comments:

Post a Comment